ARE YOU FAKE?

PARSONS DESIGN & TECH MFA THESIS

Over the course of my last year at Parsons,

I used my thesis to explore this question : what does it mean to express ourselves authentically online? The exercises I have developed, which take the the form of chrome extensions and critical designs, have become practiced-based research into this question. Each allowed me to procure conclusions about how millennial users define online behaviors as either “real” or “fake” and how current online systems and their interfaces may be contributing to certain conceptions. Ultimately, my aim is to challenge mainstream definitions and expectations of what it means to portray an authentic identity online (AKA “being real”).

“Ultimately, my aim is to challenge mainstream definitions and expectations of what it means to portray an authentic identity online (AKA “being real”).”

Prototype 1: PHYSICAL FILTERS

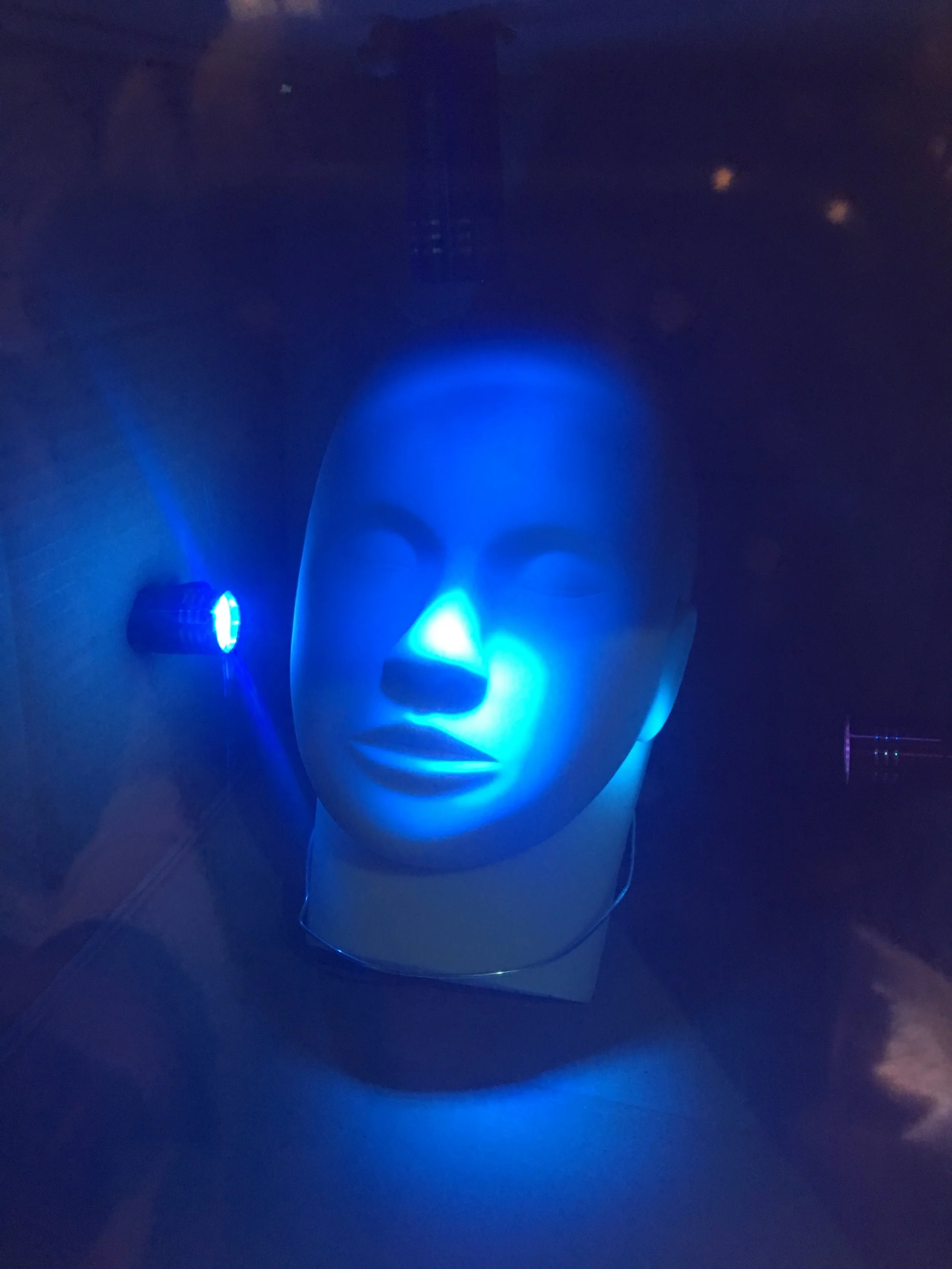

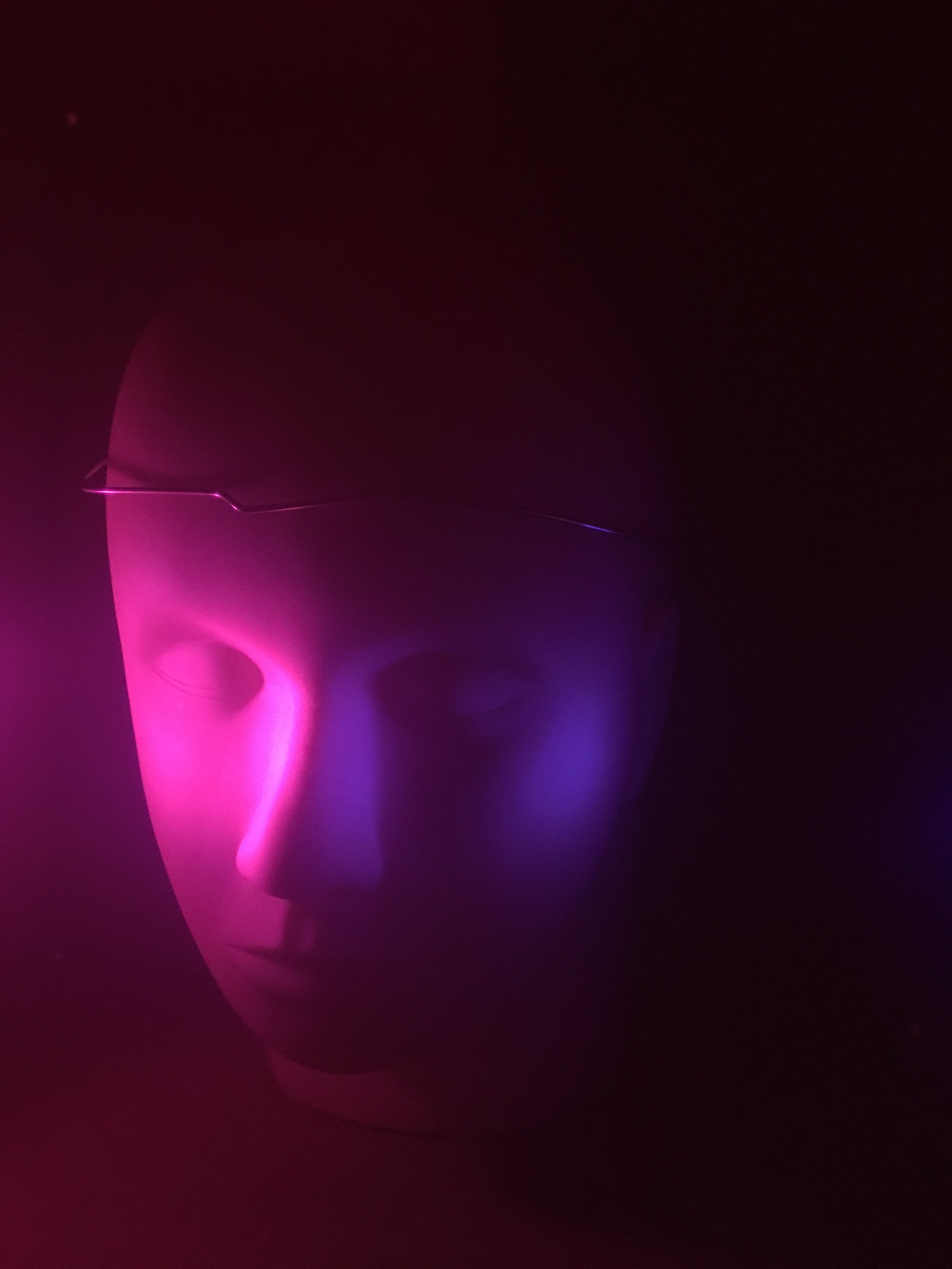

There is sentiment in our culture (see documentary Miss Representation) that before digital tools, images were more “authentic”; and for young people producing images online today, the mechanical origins of the digital editing tools we see and manipulate may not be apparent. Therefore, through my first prototype, I hoped to make visible the very physical tools that have been used to manipulate images since photography’s founding and encourage participants to question if images have ever been truthful, online or offline?

As a prompt, I built a portable “photo studio”. The studio consisted of a cardboard box with a mannequin head inside. And I asked the participants to take the best portrait they could of the mannequin head using the tools I provided: filters made of colored, transparent papers, lights on the sides and top of the box that could be turned on/off or slide back and forth, and my camera phone. The participants were not allowed to use any digital tools to manipulate the photos, only the physical tools I provided. I wanted to reduce photography down to its humble beginnings to better outline the processes originally used to manipulate images.

Prototype 2 : TOO MUCH

I first became interested in the idea of online “authenticity” when watching makeup tutorials and following the Instagram models who produce them. Often in the comment sections of their pages and videos, users called these women “fake”, inauthentic, deceptive, or “curated”, criticizing them often because their offline and online identities did not align. In order to challenge the inconsistent ways we define “authenticity” online, I created a performance piece called Too Much. I wanted to question this system of judgement and also make the argument that the internet should allow us to explore the various facets of our identities.

In the experiment, I have participants go to a YouTube page and watch a video tutorial of me applying makeup. I begin the video with a make-up free face and begin applying as I normally would. About 1/3rd through the eight-minute video, I start to oscillate between traditional and nontraditional means of manipulating my image or representation.

Throughout the video, participants can click on a button reading “too much” to indicate when they feel my makeup is excessive or inappropriate through a chrome extension I built. I chose the phrase “too much” because it is a popular phrase seen often in the comment boards under videos where women are doing their makeup or expressing themselves in ways that are seen as performative or attention-seeking. When the button “too much” is pressed, the current frame of the video is selected and stored below the video, hidden from the participant until the end of the viewing.

Final : REAL SCORE

The study born of Too Much would be Real Score, a critical design and chrome extension built to test the attitudes of my participants. Real Score determines how “real” your identity is online. I wanted to create something that parodies the notion that an “authentic” identity is a consistent one. Therefore, Real Score takes in a picture taken recently by someone else and a selfie you have recently posted or taken yourself. Using these photos, one taken the way others see you and another taken the way you see yourself, Real Score generates a score assessing how “real” or “authentic” your online persona is.

Behind the scenes of the application, I am using Kairos Facial Recognition API to determine how likely the two photographs are of the same person, and using that number as the “Real Score”. The higher the API’s confidence that the two pictures are the same, the higher your score. The extension then takes the score and attaches it to every picture on your profile (sort of like a scarlet letter), so that you can imagine others seeing the score and judging you accordingly.

Findings

Usually Real Score was tested with one per-son at a time. I chose individuals who were active on instagram and often posted “selfies” (pictures taken of you, by you). All of the participants were millennials and the pool was 40% men and 60% women with ten participants in total. I would only introduce the exercise by saying that this application would tell them “how real they were online”.

Most of the participants were unhappy with any score they received that was below 60% despite it being a somewhat arbitrary number. I could conclude from the study a few basic premises: 1) people generally saw be-ing too “fake” or not “real” enough as a bad trait for their online profiles and were mindful of treading the line between revealing and concealing certain information 2) still every-one admitted to managing their audiences’ impressions of them through posting certain images over others. Majority of the participants said they would be embarrassed if their score was revealed to others online and acknowledged that instagram allowed for impression management and image manipulation. A female participant, aged 24, said that her Instagram, “Is not a daily channel. It’s like the life I’m trying to maintain and that’s why the photos on Insta-gram are different from my other social media.”

At least five participants said that if Real Score was mandated, they believed most people would stop posting photos online all together. Of imagining Real Score as an actual practice, one participant, a 25-year-old man, said it was a “scary” idea because he believed that changing your identity online was “the whole point”.

All participants with scores at or below approximately 65% wanted to know the scores of others or were relieved to find they were near the average participant score of 65%.